Portfolio

Filter by Category

Filter by Date

Search

I have been a professional freelance writer for more than 20 years and have written for a variety of publications and companies including Better Homes and Gardens, GE, Intel and The Washington Post. If you’re looking for high quality, professional writing tailored to you and your style, I deliver outstanding results.

Gunther’s role in SGIP changing along with group’s structure

Southern Company Devises Automated Method to Monitor Capacitor Bank Health

Revere Security Cryptographers Build on German Enigma Code

Cryptographers at Revere Security in Dallas have developed a cost-effective algorithm that is smart enough, short enough and fast enough to protect smart meters from hackers and terrorists, CEO Rich Stephenson told us recently. The firm devised the algorithm, called Hummingbird, in part by using simple but highly effective algebra.

The next hurdle will be persuading utilities to adopt the new encryption technology, said Chris Hanebeck, Revere’s VP of product marketing. Because the approach to encryption is so different from current systems, and utilities do not like to be the first to spend cash on new technology, “everyone is racing to be second,” he said.

Revere founder Eric Smith and two fellow researchers began working on cryptography about 10 years ago, backed by a few small investors, Stephenson said. Smith’s group started on the technology that would become Hummingbird in 2005, with funding from the Department of Homeland Security. Revere raised VC and incorporated in 2008. It now has 14 employees.

A key addition was Whitfield Diffie, best known for the invention of public key cryptography. Diffie, former chief security officer for Sun Microsystems, joined Revere Security in 2009. “He’s definitely a rock star in the small community of cryptographers,” Stephenson said. “He brought different ways of looking at Hummingbird to the company.”

For smart meters, the challenge is to fit in the encryption without overwhelming the meters’ primary function, Mitchell Thornton, professor of computer science and engineering at Southern Methodist University, told us. SMU is performing independent tests of Hummingbird for Revere.

Instead of adapting existing encryption technology designed for computers, Hummingbird was developed specifically for small, resource-constrained devices like smart meters, sensors and smart cards, Stephenson said.

Code designed for computers uses complex differential calculus and modal math. But resource-constrained devices don’t have the computational capabilities, memory or power supply to support such advanced math. Revere researchers have found a way to make algebra do the job using what are called fixed numbers, say 2.8, as opposed to floating numbers, such as 2.8 x 10 to the 32nd power, Thornton said.

Hummingbird’s algorithm is so efficient in terms of power use, memory and speed that it can run on an 8- or 16-bit microprocessor, Revere said. Similar software used in Itron Open Way smart meters uses more complex math and requires a 32-bit microprocessor, Stephenson said. “With Hummingbird being as small as it is, we can go back and retrofit existing smart meters that have been deployed,” Stephenson said.

That is a key issue, since many security experts have argued that current smart meters are not protected from hackers and terrorists. A skilled attacker could, Thornton said, turn off power to one home or an entire area and demand ransom; program smart meters to shave 10% off a customer’s usage; overload relay switches and cause fires in specific cases; or even shut down the grid in an entire nation.

QUOTE OF THE DAY: In public forums, you hear a lot of utilities saying: “We’ve got it covered. Security is not an issue.” What you hear in private is different. – Chris Hanebeck, Revere’s VP of product marketing

Revere is testing whether it is best to employ Hummingbird as hardware, software or a combination of the two, said Thornton, the SMU professor.

German code helped

Hummingbird’s design was inspired by the German Enigma code machine, which used rotors to encode messages before and during World War II. Computer encryption by necessity uses complex math. Smith improved on the Enigma concept using four simulated rotors instead of three real ones, allowing for the rotors to run in random instead of sequential order and creating a code that is harder to break. One of Diffie’s key contributions was much-simplified math, Stephenson said.

“Just because it’s based on Enigma doesn’t mean it’s only as good as Enigma,” Thornton said. Polish code breakers cracked Enigma just before World War II. “Using the principles of Enigma, Hummingbird is able to perform stronger encryptions than an Enigma machine. We can make the rotors go forward or backward. We can scale it up.”

SMU has been testing smart grid-related security for several years. “We have contracts with big, three-letter government agencies as well as small commercial concerns,” Thornton said. SMU researchers began testing Hummingbird four months ago and plan to continue tests for six months.

“So far I have not found a case where Hummingbird isn’t as good as or better than standard encryption,” Thornton said. “And I have reason to believe it’s going to be equivalent to or better than other standard encryption methods, but I haven’t fully verified it yet.”

Market yet to come

Revere is expected to turn its first profit this year, but not principally because of Hummingbird, said CEO Stephenso. The firm is splitting its focus evenly between Hummingbird and similar technology to protect RFIDs, for which there is a more ready market, he said. “They’re essentially fancy barcodes, and companies such as Wal-Mart use them to track containers,” he said.

Revere will be ready to support Hummingbird later, when utilities start adopting it, Stephenson said. “We’re just now getting into the [utilities] market. The biggest obstacle is that Hummingbird is not considered one of the standard algorithms.”

Walmart Nets Millions from DR, Automated Shopping by Sunlight

Smart Grid Today / Published 2011 / By Karen Haywood Queen

Walmart shoppers likely will not even notice when the air-conditioning setting at their local store bumps up 4° to 78° for several hours during peak demand periods this summer. But when a company as big as Walmart, the largest private employer in the US, takes action,the reduction in demand across the grid is significant.

Walmart has DR programs in place at 1,300-1,400 of its 4,400 US stores, Jim Stanway, the giant retailer’s senior director of global energy services, told us Monday. “Per store, we can briefly put 300-400 KW back onto the grid [by decreasing usage] when we go to demand response,” Stanway said. If each store hit even one DR period in the same week, the reduction in demand across the country would be as high as 470,000 KW for that week.

For the past four or five years, the retailer has been part of DR programs with utilities across the country, he said. The system works by linking a real-time energy data system to each store’s building controls. Most of the temperature adjustments are automatic.

Customers likely do not notice the change because it takes a few hours for the temperature to increase when the setting is changed. By then, the DR period is usually over, Stanway said.

The retailer has been working to reduce its carbon footprint and bolster its green credentials through energy-saving measures and the use of alternative energy such as thin-film solar. But the main impetus for participating in such programs is to save money. Walmart declined to release its savings.

The company has real-time energy- use systems in 1,500 stores, Stanway said. “That gives us electricity consumption at the main meter and sub-circuit levels in mostly 15-minute increments and some three-minute increments,” he said.

The real-time energy data also is useful for studying the impact of Walmart’s energy-efficiency measures, Stanway said. “When we do a lighting retrofit, we can use the real-time data to study energy consumption before and after, to make sure [that] installations were done properly and [that] we get a good return on investment.”

Walmart has what it calls a daylight- harvesting program at its stores built since 1996, Stanway said. Between 2,500 and 3,000 stores have the system, which includes skylights and sensors to detect the amount of sunlight.

“Whenit’sanice,sunnyday,thesensors in the store detect the amount of sunlight and feed that data through our control system. It dims the lights,” Stanway said. “If it’s bright enough outside, the lights will actually go off. If a cloud drifts over halfway through the day, the system will adjust and the lights will start coming back on. The way it’s designed, it’s a gradual change and invisible to the customer.”

Initially the challenges included a delay of up to 15 minutes for the lights to react to the sunlight sensors,Stanway said. “Now we’re down to a few seconds,” he said. The system is made by Novar, which has a Walmart support center in Bentonville, Ark, the retailer’s headquarters.

Daylight harvesting can save up to 75% of the electric-lighting energy used by a Walmart store during daylight hours, he said. Walmart declined to disclose the cost of the system or the payback time, but each system can save an average of 800,000 KWH/year, Stanway said. At 10¢/KWH, that is $80,000/year per store. With daylight-harvesting systems in 2,500 stores — the low end of the company’s estimate of how many stores have the system — that is a companywide savings of up to $200 million/year.

Walmart also has centralized monitoring of energy use in each store, with alerts when use rises beyond normal limits. Issues that might warrant an alarm include a refrigerator case left open, Stanway said. “The system issues alarms when something is outside parameters,” he said. “Some things can be adjusted and corrected remotely.” If it cannot be fixed remotely, a technician is sent to fix it.

“Walmart’s leadership is important — they’re demonstrating that energy management is cost effective,” Miriam Horn, director of the Environmental Defense Fund’s (EDF) smart grid initiative, told us yesterday. “Walmart got ahead of the rest of the world because they put in a lot of advanced energy-management technology. Having Walmart show the way has been really important.” The EDF has a presence in Bentonville to work more closely with the retailer, she said.

Walmart is participating in DR programs in at least 10 states, Horn said. The company has also installed advanced meters in some stores at its own expense. “They make the important point that for this to work for anybody, they have to have the data and pricing information,” she said.

Having the right incentives make a key difference, too. “In our conversations with Walmart, they’ve made the point that they’re rolling out the technology where the return on investment is best,” Horn said. “They do have a business case for making these investments. They have a plan to keep expanding. In each case, it depends on the policies at the utility, state and ISO level to determine whether there’s a business case for Walmart to do it.”

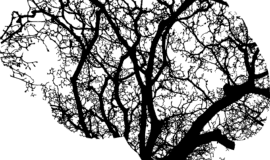

Tree of Life: Giving People with Brain Injuries Hope and a Future

When “Lisa” came to Tree of Life in 2002, she drank too much, needed psychiatric care for depression, could not walk up steps or on uneven ground, had gained 50 pounds and needed 24-7 care because of her brain injury, suffered in a car accident. Now Lisa, who wishes to remain anonymous, has lost the weight, gained a boyfriend, conquered the drinking problem and run a 5K. She works part time in retail and lives in a supervised apartment.

Lisa and others who’ve suffered traumatic brain injury say they have been transformed by a comprehensive rehabilitation program at Tree of Life, a private facility for brain injury patients located in Richmond.

Lisa originally went to a residential facility and outpatient rehab in Michigan, where she lived at the time of her accident, say her parents, who live in Williamsburg. But instead of getting the help she desperately needed, Lisa was raped by one of the center’s drivers.

“She was so without hope [after that] that she said she no longer wanted to live,” says Lisa’s mother. “She was extremely depressed. She was extremely damaged mentally.”

So Lisa’s parents, who, because of the nature of their daughter’s injuries, have also requested anonymity, began looking for another place where their daughter could at least be safe and possibly rehabilitated.

“We went to see a lot of places in Michigan,” says Lisa’s father. “Every one we saw was like a dog kennel. People were just shoved into rooms. They didn’t even have their sheets changed sometimes. Basically, it was a storehouse for damaged people.”

Then they found Tree of Life. “We were welcomed with open arms,” says Lisa’s father. “The house was very warm, very family-oriented. The people who spoke to us were so kind, so welcoming. I knew this was the place where she could recuperate.” An added bonus: Tree of Life is less than an hour’s drive from their home in Williamsburg.

Internationally known neuro-rehabilitation physician Dr. Nathan D. Zasler started Tree of Life in 1997 with a five-bedroom house and one patient. The goal: to help people with brain injuries achieve as much independence as possible. Zasler teaches in the departments of physical medicine rehabilitation at both Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Virginia schools of medicine and has lectured and written extensively on the unique challenges of rehabilitating brain injury patients.

Zasler saw the need for a long-term program, one that worked with such patients beyond the acute rehab and therapy patients receive immediately following an accident or other event that caused the brain injury.

Tree of Life has grown to a full staff including physical therapists, cognitive behavioral therapists, neurorehabilitation psychologists and others. During the day, staff-to-patient ratios are at least one-to-one, Zasler says.

Tree of Life is not a hospital, nursing home or adult day care center. Therapy works toward getting patients back into the community as fully as possible. Patients come from all over the East Coast and as far west as Illinois and Michigan, he says.

A typical day might include formal one-on-one therapy, a group therapy session, recreation time, music, art, and a meal out at a restaurant. Average transitional length of stay is six to 12 months.

The cost is high—about $650 a day. But that cost includes room and board and more important, 24-7 access to Zasler, Tree of Life’s medical director, and Dr. Michael F. Martelli, director of neuropsychology. A patient who needed 24-7 supervision from a certified nurse assistant might pay almost $400 a day, not including room and board, Zasler says.

The recovery time for people with brain injuries is longer than usually funded by commercial or government insurance, Zasler says, so almost all of the patients rely on workers’ compensation to help pay for care. “Unfortunately for people with these type of injuries, insurance won’t pay for long-term care or transitional care,” he explains.

Among Zasler’s goals: to educate private and federal insurance programs across the country about the many benefits of neuro-rehabilitation services. Even though a rehabilitated patient may still be considered 100-percent disabled and not necessarily able to get a job on his or her own, even a part-time job and the social life enabled by the program offers a huge benefit.

“It’s more than just the financial benefits of working,” Zasler says. “There are the psychological benefits, the social benefits. Many of these people with brain injuries are socially isolated. We’re getting these people out of their homes and into the community.”

Lisa is still in the program, living mostly independently in one of Tree of Life’s apartments. She still needs the supervision, her parents say. “But if you would talk to her now, you might not even know she had a brain injury,” her mother says. “Her recovery is absolutely a miracle. Yes, it’s due to her efforts. It’s also due to Tree of Life. They gave her hope. It’s an incredible transformation.”

Tree of Life employs the “bio-psycho-social” model in treating patients—another way to say the program approaches treatment from the physical, emotional and social aspects (i.e., treating the “whole person”).<b> “We want to understand who the person was before their injury,”</b> Zasler says. “One of the mistakes other programs make is they don’t take enough time to figure [that out].”

Home that Afternoon: New Techniques and Technology, Cost Pressures Drive Transition to More Outpatient Procedures

Almost 25 years ago, Kathy Santini had to have open abdomen surgery to remove her gallbladder. Laparoscopic gallbladder surgery, where the surgeon makes a few puncture marks and removes the organ through the belly button, was a new technique that many surgeons weren’t yet using.

“I was in the hospital four or five days,” says Santini, now vice president of surgical services at Bon Secours Richmond Health System. “I had to be off work for six weeks so the lining under my skin could close and heal. And I could work only half days at first. I had a bunch of restrictions. Once you open someone’s abdomen, you’re affecting a lot of systems. It was a big deal.”

Today, 54 percent of gallbladder removal patients have outpatient surgery, meaning they are able to go home within 23 hours, according to a 2010 report for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Looking beyond gallbladders, 63 percent of all surgery patients in hospitals did not have to stay overnight in 2005, compared to 51 percent in 1990 and just 16 percent in 1980, the AHRQ says.

Any surgery is still a big deal. But new surgical techniques and technologies that minimize incision size, blood loss and tissue trauma have made faster recoveries possible, says John S. Hudson, director of surgical services at Sentara CarePlex Hospital in Hampton. For example, a laparoscope—a long metal tube with a camera lens at the end— allows a surgeon to see what he or she is doing without having to make a long incision. In some cases, a surgeon is able to remove the tissue or affected organ through one of the body’s natural openings.

Often, the benefits of the new techniques go beyond just avoiding a stay in the hospital. Patients who have laparoscopic procedures generally return to normal function and work several weeks earlier, Hudson says.

The cost factor

The other factor driving the shift to outpatient surgery is pressure on insurance companies and other third-party payers such as Medicare and Medicaid to reduce rising health care costs, according to the AHRQ and physicians.

“A lot of this got driven by the insurance business,” says Dr. Wilhelm Zuelzer, Chief of Perisurgical Services at VCU Health Systems in Richmond. “It’s ultimately cheaper to do an outpatient surgery rather than inpatient.”

Across the board, the mean charge for all ambulatory surgeries was $6,100 compared to $39,900 for inpatient surgeries, the AHRQ says. But it’s difficult to make an exact comparison between the same surgery done as an outpatient and inpatient basis because surgeries and patient conditions that do require a hospital stay are, by their very nature, more complicated and likely to be more expensive.

Patients can get outpatient surgery in hospital outpatient centers and in a growing number of stand-alone outpatient surgery centers. Since the stand-alone ambulatory surgery centers don’t have the added expenses of hospital emergency rooms and critical care units, they can offer even more savings compared to a hospital outpatient department, notes Jay Schukman, regional vice president

and medical director with Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield in Virginia.

Top outpatient procedures

The top six outpatient surgeries and procedures performed in ambulatory surgery centers billed to Medicare in 2009 were all related to cataracts and digestive tracts. Procedures done on the eye, ear, nose and mouth were predominantly outpatient.

Colonoscopy and biopsy was the most commonly performed outpatient procedure, an AHRQ study found. About two-thirds of procedures on the skin, digestive tract and urinary tract were outpatient, AHRQ says.

The most significant shifts in the last decade have been in the areas of gynecology and general surgery, due to the use of laparoscopic techniques, Hudson says. Gynecologists now perform hysterectomies using a total laparoscopic approach, allowing women to go home the same day and often return to work within a few weeks. The once common tubal ligation for prevention of pregnancy is now rare, replaced by a simple procedure performed in the doctor’s office, he says. Weight loss lap band surgery is also being done on an outpatient basis, he says.

Dr. Gregory FitzHarris, a colon and rectal surgeon at Sentara Surgery Specialists in Hampton, is enthusiastic about a less invasive technique for removing large polyps in a patient’s mid to upper rectum, lesions that are too far up to reach with a retractor. With the old technique, the surgeon opens up the patient, remove a portion of the rectum and resections the rectum. The patient stays in the hospital three days to a week and is off work four to six weeks. Using the newer technique (official name: transanal endoscopic microsurgery), the surgeon blows up the rectum with carbon dioxide and removes the polyp. The patient is usually back to work within two days, he says.

“I just did one lady and I finished the surgery around 10:30 a.m. and she went home around 3 p.m.,” FitzHarris says. “Most leave the same day. There’s very little pain involved and very little disability.”

Patient selection is important

Outpatient surgery isn’t for every procedure or every patient. People who are older or obese and have what doctors call core morbidities—high blood pressure, diabetes and heart problems. “We have to fine tune the outpatient surgery,” Zuelzer says. “You have to individualize it. You have to look at the home situation.”

A younger, healthier patient with good social/family support may be able to have procedures done on an outpatient basis that an older patient with chronic conditions and poor social support may not, Hudson says. Important considerations are pain management, post-procedure monitoring and therapies, and insurance coverage.

“There’s no reason for a patient to be in the hospital if he doesn’t need to be,” says Shirley Gibson, interim vice president of nursing for VCU Health System. “The hospital is a very expensive place to be. [However, with] inpatient you have nurses there always, you have the labs there always. You can look in on the patient, pay attention to nuances.”

If a patient doesn’t have family or friends who can step in and help, the patient may be transferred from the hospital to a skilled nursing care facility instead of going home, at about one-eighth to one-tenth the cost of a hospital, Schukman says.

Doctors, their patients and hospitals don’t always have much choice—at least if they want the extra time in the hospital to be reimbursed by the patient’s insurance company. “It’s not where somebody can say ‘I want to stay in the hospital three days,” Zuelzer says. “A herniated disc used to be three days in the hospital. Now it’s considered a 23-hour outpatient procedure. If the patient or doctor says ‘I don’t feel comfortable going home today’ it’s still a battle with insurance.”

Some in the medical field worry that too much pressure is coming from health insurance companies to save money by discharging patients quickly. For example, Santini says the hospital has just been informed by an insurance company that laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery is now an outpatient procedure. That means the hospital now has to negotiate with the insurance company for every patient they feel needs to be hospitalized.

“If a procedure is designated outpatient by a third party payer and you’re there for 48 hours, you’re still an outpatient,” Santini says. “They call that ‘an outpatient in a bed.’”

Physicians can advocate for insurance companies to cover a longer stay, but often, “They’re not going to reimburse for more than they pay for an outpatient procedure,” Santini says. “Outpatient rates are obviously a lot lower than inpatient rates. For a procedure that has been polled as outpatient, we sometimes don’t come anywhere near making the cost, let alone breaking even or making a profit.”

On the flip side, some patients have requested to remain in the hospital solely for convenience, says Schukman says. “Someone might say, ‘My husband doesn’t want to take off work today to pick me up, so I’m going to stay overnight and he can pick my up tomorrow. When they’re paying several thousand dollars a day for a hospital room, it’s not appropriate to stay for convenience. You’re paying that bill and we’re all paying that bill in our insurance rates.”